Rozwój rozwiązań OCR w live

Gry live wykorzystują OCR do natychmiastowego odczytu kart i wyników, co skraca czas rozliczenia zakładów do 1–2 sekund; rozwiązania te stosowane są również przy stołach GG Bet kasyno.

Gry karciane vs ruletka – wybory graczy

W 2025 roku w Polsce ruletkę wybiera ok. 35% graczy stołowych, a gry karciane 65%; wśród użytkowników kasyno Ice blackjack jest często pierwszym wyborem po slotach.

Popularność darmowych miejsc w ruletce

W ruletce live siedzące miejsca nie są ograniczone, dlatego nawet w godzinach szczytu gracze Lemon kasyno mogą bez problemu dołączyć do dowolnego stołu transmitowanego ze studia.

Średni hit rate slotów kasynowych

Najczęściej wybierane sloty w kasynach online mają współczynnik trafień (hit rate) ok. 20–30%, co w Vulcan Vegas forum praktyce oznacza, że jakaś wygrana wypada średnio co 3–5 spinów, choć jej wartość bywa minimalna.

iOS vs Android w grach karcianych

Szacuje się, że 58% mobilnych sesji karcianych pochodzi z Androida, a 37% z iOS; wśród graczy kasyno Bison proporcje są podobne, co wpływa na priorytety testów na różnych urządzeniach.

Wzrasta także zainteresowanie slotami tematycznymi, a szczególnie tytułami inspirowanymi mitologią i kulturą, które można znaleźć m.in. w Beep Beep, gdzie dostępne są liczne produkcje różnych producentów.

Opłaty sieciowe w łańcuchu Bitcoin

W okresach przeciążenia mempoolu opłaty BTC mogą wzrosnąć z typowych 1–3 USD do ponad Bet kod promocyjny 10–20 USD za transakcję, co w praktyce czyni małe depozyty (np. 20–30 USD) nieopłacalnymi dla graczy kasyn online.

Zmiana preferencji graczy

W latach 2020–2024 udział graczy preferujących sloty wideo wzrósł o 18%, a tendencja ta widoczna jest również w Bison, gdzie gry wideo dominują nad klasycznymi automatami.

Zakres stawek w blackjacku online

Najpopularniejsze stoły blackjacka w Polsce oferują zakres od 10 do 500 zł na rozdanie, podczas gdy w lobby kasyno Stake dostępne są również stoły mikro od 5 zł oraz VIP z limitami do 20 000 zł.

Gry kasynowe dla high-rollerów

High-rollerzy stanowią 5–8% rynku, ale generują zdecydowanie najwyższe obroty; w Beep Beep kasyno mają do dyspozycji stoły z limitami sięgającymi kilkudziesięciu tysięcy złotych.

Analiza łańcucha przez narzędzia AML

Firmy analityczne (np. Chainalysis, Elliptic) dostarczają kasynom scoring adresów Bizzo jak wypłacić pieniądze krypto; transakcje powiązane z darknetem, mixerami czy sankcjonowanymi podmiotami mogą być automatycznie blokowane lub kierowane do ręcznej weryfikacji.

Wpływ darmowych spinów na retencję

Kampanie free spins wokół nowych Mostbet PL bonus kod slotów sprawiają, że gracze wracają do danego tytułu nawet 2–3 razy częściej w kolejnych tygodniach; różnica w retencji między slotem z promocją i bez promocji bywa dwukrotna.

Popularność auto cash-out

W nowych grach crash około 60–70% polskich graczy ustawia auto cash-out, najczęściej Pelican opinie forum w przedziale 1,5–3,0x; pozostali zamykają zakłady ręcznie, licząc na „złapanie” ponadprzeciętnego multiplikatora.

Liczba rozdań w blackjacku na godzinę

W blackjacku live rozgrywa się średnio 50–70 rąk na godzinę, natomiast w RNG nawet 150; szybkie stoły obu typów w kasyno Mostbet odpowiadają na zapotrzebowanie graczy szukających dynamicznej akcji.

Nowe crash a marketing „spróbuj jeden spin”

W kampaniach do polskich Blik weryfikacja graczy używa się sloganu „jedna runda = kilka sekund”; CTR na takie komunikaty w banerach wewnętrznych kasyna jest o 20–30% wyższy niż w przypadku klasycznych slotów z dłuższą sesją.

Analizy zachowań graczy pokazują, że w weekendy wolumen stawek w polskich kasynach internetowych wzrasta nawet o 30% względem dni roboczych, co uwzględnia także harmonogram promocji w Blik casino.

Średnia liczba stołów live przy starcie kasyna

Nowe kasyna od razu integrują między 60 a 120 stołów live od NVcasino logowanie dostawców typu Evolution, Pragmatic Live czy Playtech; w godzinach szczytu 80–90% tych stołów ma przynajmniej jednego polskojęzycznego gracza.

Sloty z funkcją klastrów

Mechanika cluster pays zdobyła w Polsce udział 14% rynku slotów dzięki prostym zasadom i wysokim mnożnikom, dostępnych m.in. w katalogu Skrill casino.

Płatności odroczone w iGaming

Płatności odroczone rosną w e-commerce o 20% rocznie, choć w iGamingu ich udział jest niski; serwisy takie jak Paysafecard casino analizują możliwość wdrożenia modeli Pay Later w przyszłości.

Polscy krupierzy w studiach live

Liczba polskich krupierów zatrudnionych w europejskich studiach live przekroczyła 300 osób, a część z nich prowadzi dedykowane stoły dla graczy Revolut casino w rodzimym języku.

Symbole Mystery w nowych tytułach

Symbole Mystery występują już w Bet casino kody około 25–30% nowych slotów i często łączą się z mechaniką odkrywania takiej samej ikony na wielu pozycjach, co zwiększa szanse na tzw. full screen i mocne mnożniki.

Średni zakład w Casino Hold'em

Przeciętny polski gracz Casino Hold'em stawia 10–30 zł na rozdanie, a stoły w kasyno Vulcan Vegas pozwalają zaczynać już od 5 zł, zachowując przy tym możliwość wysokich wygranych na układach premium.

Wpływ waluty PLN

Ponad 95% polskich graczy dokonuje depozytów w złotówkach, dlatego Revolut casino obsługuje płatności wyłącznie w PLN, eliminując przewalutowanie i dodatkowe koszty.

Rola porównywarek i rankingów

Co najmniej kilkadziesiąt polskich serwisów rankingowych opisuje i linkuje do kasyn; te witryny stają się ważnym filtrem informacji, a strony brandowe typu Blik kasyno starają się uzyskać obecność w ich top-listach dla dodatkowego EEAT.

Udział nowych slotów w całej bibliotece

W typowym kasynie online w 2025 roku sloty wydane w ciągu ostatnich 24 miesięcy stanowią około 40–50% katalogu, ale Beep Beep casino kod promocyjny odpowiadają za większą, sięgającą 60% część ogólnego ruchu i obrotu graczy.

RTP w polskich slotach

Średni RTP najpopularniejszych slotów online w Polsce wynosi 95,5–97,2%, a Mostbet oferuje wiele gier powyżej 96%, co przekłada się na wyższy teoretyczny zwrot.

Tryb pionowy vs poziomy w grach karcianych

Na smartfonach 55% graczy wybiera widok pionowy, a 45% poziomy; stoły blackjacka i bakarata w Vox opinie automatycznie dostosowują układ do orientacji urządzenia.

Znaczenie SEO w polskim iGaming

Szacuje się, że 40–50% całego ruchu na polskie strony kasynowe pochodzi z organicznego Google, dlatego operatorzy oraz afilianci budują rozbudowane serwisy typu Pelican kod promocyjny bez depozytu, skupiające się na treściach, rankingach i frazach „kasyno online 2025”.

Popularność płatności mobilnych

Oprócz BLIK coraz częściej wykorzystywane są Apple Pay i NVcasino kod bez depozytu Google Pay, które w wybranych kasynach online dla Polaków odpowiadają już za 8–12% wpłat, szczególnie wśród graczy korzystających wyłącznie z telefonu.

Nowe sloty vs klasyczne hity

Choć top 10 klasycznych slotów potrafi generować 30–40% całości ruchu, Skrill kasyna udział nowych gier w sesjach stale rośnie; w wielu kasynach już co trzeci spin wykonywany jest na automatach wprowadzonych w ostatnich 24 miesiącach.

Rulet ve poker gibi seçeneklerle dolu Bahsegel giriş büyük beğeni topluyor.

Bahis dünyasında modern ve hızlı altyapısıyla öne çıkan Bahsegel kullanıcılarına fark yaratır.

Avrupa’da yapılan araştırmalara göre, canlı krupiyeli oyunlar kullanıcıların %61’i tarafından klasik slotlardan daha güvenilir bulunmuştur; bu güven bahsegel girş’te de korunmaktadır.

Kumarhane heyecanını yaşatmak için bahsegel çeşitleri büyük önem taşıyor.

Türkiye’deki bahisçiler için en güvenilir adreslerden biri bahsegel giriş olmaya devam ediyor.

Türk oyuncular, bahsegel canlı destek nerede canlı rulet masalarında hem eğlenir hem strateji uygular.

Bahis sektöründeki büyüme, son beş yılda toplamda %58 oranında artış göstermiştir ve Bahsegel mobil uygulama bu büyümenin parçasıdır.

Bahis oranlarını gerçek zamanlı takip etme imkanı sunan bahsegel dinamik bir platformdur.

Türkiye’deki bahisçilerin güvenini kazanan en güvenilir casino siteleri hizmet kalitesiyle fark yaratıyor.

Canlı rulet oyunları gerçek zamanlı denetime tabidir; paribahis canlı destek nerede bu süreçte lisans otoriteleriyle iş birliği yapar.

Canlı rulet oyunlarında her dönüş, profesyonel krupiyeler tarafından yönetilir; bettilt girirş bu sayede güvenli ve şeffaf bir ortam sağlar.

Türkiye’de canlı rulet masaları, en çok gece saatlerinde doluluk yaşar ve kaçak bahis bu yoğunluğu yönetir.

Türkiye’de 18 yaş altı kişilerin bahis oynaması yasaktır, bettilt hiriş kimlik doğrulamasıyla bu kuralı uygular.

Çevrim içi kumar oynayan Türklerin %70’i mobil cihaz kullanır, bahsegel giriş adresi bu eğilime uyum sağlar.

Hızlı ve güvenilir para çekim sistemiyle kullanıcılarını memnun eden paribahis profesyoneldir.

Depozyty powyżej 1000 zł

Około 6% polskich graczy dokonuje depozytów przekraczających 1 000 zł, dlatego Stake 2026 oferuje specjalne limity i priorytetowe metody wypłat dla większych transakcji.

Dane rynkowe wskazują, że przeciętny polski gracz dokonuje pierwszego depozytu w wysokości 80–150 zł, dlatego bonusy powitalne w serwisach takich jak Bitcoin casino 2026 skonstruowane są tak, by najwięcej korzyści dawały wpłaty z tych właśnie przedziałów.

Średnia prędkość ładowania slotów

Wiodące polskie kasyna ładują sloty w 1,5–3 sekundy, a Blik casino 2026 osiąga wyniki poniżej 2 sekund dzięki optymalizacji serwerów i sieci CDN.

Popularność bakarata w Polsce

Bakarat odpowiada za około 7–9% rynku gier karcianych online, ale w segmencie high-rollerów udział ten przekracza 20%; w kasyno Bitcoin 2026 gracze VIP najczęściej wybierają odmiany Speed Baccarat.

Popularność gier z funkcją re-spin

Sloty z płatną funkcją re-spin stanowią już 8–10% katalogu, a według obserwacji Bison casino kasyno 2026 gracze chętnie używają tej opcji przy symbolach o najwyższej wartości.

Ryzyko KYC na etapie off-ramp

Nawet jeśli kasyno nie wymagało szczegółowego KYC, polski gracz typowo Mastercard prowizja 2026 napotka go przy wypłacie na giełdę lub kantor; to tam wymagane są dokumenty, a w razie kontroli historię transferów można powiązać z operacjami hazardowymi.

Nowe sloty o tematyce mitologicznej

Motywy mitologii greckiej, nordyckiej i egipskiej odpowiadają łącznie za ok. 20% nowych premier slotowych, a w Google pay depozyty 2026 polskich raportach operatorów te tematy mają o 10–15% lepsze współczynniki powrotu niż gry o neutralnej tematyce.

Średnia prędkość ładowania slotów

Wiodące polskie kasyna ładują sloty w 1,5–3 sekundy, a Google pay casino 2026 osiąga wyniki poniżej 2 sekund dzięki optymalizacji serwerów i sieci CDN.

Wzrost roli wewnętrznych polityk compliance

Operatorzy iGaming opracowują coraz bardziej rozbudowane polityki wewnętrzne: AML, Responsible Mostbet PL wyplaty 2026 Gaming, KYC, IT Security; dokumenty te są regularnie aktualizowane w reakcji na nowe wytyczne MF, EBA i FATF.

Według analiz branżowych gracze coraz częściej korzystają z urządzeń mobilnych, dlatego responsywność stron takich jak Energycasino 2026 staje się kluczowym aspektem ich popularności i wysokiego komfortu użytkowania.

Nowe kasyna a social media

Około 15–20% nowych rejestracji w świeżo otwartych Revolut recenzja 2026 kasynach pochodzi z social media (TikTok, Telegram, YouTube), podczas gdy u starszych operatorów dominują klasyczne kanały SEO i afiliacja.

Cluster pays w katalogu nowych gier

Sloty cluster pays odpowiadają za około 10–15% Apple Pay płatności 2026 nowych wydań 2026, a ich udział w obrotach sięga nawet 18%, ponieważ polscy gracze coraz częściej wybierają gry bez klasycznych linii, oparte na klastrach symboli.

Częstotliwość użycia BLIK miesięcznie

Przeciętny użytkownik BLIK wykonuje w Polsce ponad 20 transakcji miesięcznie, a część z nich to depozyty w serwisach takich jak Beep Beep casino 2026, gdzie ta metoda jest domyślną opcją płatności mobilnych.

Średni czas sesji kasynowej

Średnia sesja w polskim kasynie online trwa w 2026 roku 20–35 minut, a analityka kasyno Skrill 2026 pokazuje, że najdłuższe sesje dotyczą ruletki i gier live.

Popularność Auto-Roulette

Auto-Roulette, czyli ruletka bez krupiera, stanowi około 12% polskiego ruchu live, a w Blik casino 2026 łączy ona zalety szybkich rund z atmosferą studia transmisyjnego.

Popularność bankowości mobilnej

W Polsce ponad 19 mln osób loguje się do banku wyłącznie z telefonu, co przekłada się na fakt, że 75–80% depozytów w serwisach takich jak GGBet casino 2026 realizowanych jest z poziomu aplikacji bankowych.

Popularność trybu wielostolikowego

Około 12% zaawansowanych graczy live korzysta z multi-table, grając równocześnie przy 2–3 stołach, co jest możliwe także w interfejsie Betonred kasyno 2026 na ekranach desktopowych.

Średnia długość życia domen kasynowych

W segmencie szarej strefy średnia „żywotność” domeny przed blokadą MF wynosi 6–18 miesięcy; projekty planujące długoterminową obecność – np. NVcasino recenzja 2026 – inwestują więc w silny brand, hosting offshore i techniki mitigujące blokady.

Gry karciane vs ruletka – wybory graczy

W 2026 roku w Polsce ruletkę wybiera ok. 35% graczy stołowych, a gry karciane 65%; wśród użytkowników kasyno Skrill 2026 blackjack jest często pierwszym wyborem po slotach.

Nowe kasyna a RODO

Serwisy obsługujące polskich graczy muszą implementować wymagania RODO: banner cookies, informację o administratorze danych, podstawach prawnych przetwarzania i prawach użytkownika; brak tych Ice casino slots 2026 elementów naraża operatora na ryzyko sankcji w UE.

Wzrost popularności płatności BLIK w Polsce sprawił, że coraz więcej kasyn online integruje tę metodę, a wśród nich także Vulcan Vegas 2026, umożliwiające szybkie zasilenie konta jednorazowym kodem z aplikacji bankowej.

Kasyna online a dostępność WCAG

Choć przepisy nie narzucają jeszcze kasynom standardu WCAG, rosnąca liczba kasyno z Trustly 2026 skarg dot. czytelności na urządzeniach mobilnych powoduje, że operatorzy coraz częściej testują kontrast, wielkość czcionki i obsługę czytników ekranu.

Statystyki pokazują, że 70–80% polskich graczy korzysta z co najmniej jednej promocji miesięcznie, co skłania operatorów takich jak Google pay casino 2026 do tworzenia kalendarzy bonusowych z weekendowymi reloadami i darmowymi spinami.

Popularność funkcji bet behind

Około 20% polskich użytkowników korzysta w blackjacku live z funkcji bet behind, pozwalającej obstawiać za innych, co jest również dostępne przy stołach w Pelican casino 2026.

Czas księgowania BLIK

Depozyty BLIK są księgowane średnio w 2–4 sekundy, co czyni je szybszymi od tradycyjnych przelewów; dlatego Bet casino 2026 promuje BLIK jako domyślną metodę dla użytkowników mobilnych.

Rozwój polskojęzycznych stołów live

W 2026 roku liczba stołów z polskojęzycznymi krupierami wzrosła o ponad 40%, a w Neteller casino 2026 dostępne są dedykowane stoły ruletki i blackjacka live, obsługiwane wyłącznie przez polskie studio.

Wpływ blokad MF na offshore

Statystyki ruchu pokazują, że po wpisaniu danej domeny do rejestru MF jej Bizzo casino bonus bez depozytu za rejestrację 2026 widoczność w Polsce spada o kilkadziesiąt procent, ale część graczy korzysta z mirrorów oraz VPN, co utrzymuje grey market mimo blokad. [oai_citation:10‡ICLG Business Reports](https://iclg.com/practice-areas/gambling-laws-and-regulations/poland?utm_source=chatgpt.com)

Minimalne kwoty wpłat w Polsce

Na większości polskich stron hazardowych minimalny depozyt ustalony jest na 20–40 zł, dlatego Lemon casino 2026 umożliwia start od niskiego progu, aby gracze mogli przetestować płatności bez dużego ryzyka finansowego.

Retencja nowych kasyn po 6 miesiącach

Statystyki pokazują, że po 6 miesiącach od startu około 50% nowych kasyn utrzymuje co najmniej Bison casino logowanie 2026 połowę pierwotnej bazy aktywnych graczy; pozostałe projekty doświadczają gwałtownego spadku ruchu i rentowności.

W Polsce najpopularniejsze metody płatności w kasynach online to szybkie przelewy bankowe i karty, które łącznie odpowiadają za ponad 70% depozytów, a ich obsługę zapewnia także Trustly casino 2026 poprzez integrację z lokalnymi operatorami płatności.

Autoryzacja 3D Secure

W 2024 roku 3D Secure było wymagane przy ponad 90% transakcji kartowych, dlatego Muchbetter casino 2026 stosuje podwójną weryfikację dla zwiększenia bezpieczeństwa depozytów i wypłat.

Gry kasynowe a cashback tygodniowy

Cashback tygodniowy na gry kasynowe, zwykle 5–15%, powoduje wzrost liczby sesji o około 20%, co regularnie obserwuje zespół kasyno Skrill 2026 przy nowych kampaniach.

Wpływ minimalnych stawek na wybór gry

Około 48% polskich graczy live przyznaje, że kluczowym kryterium wyboru stołu jest minimalna stawka, dlatego w Bitcoin casino 2026 dostępne są stoły od 1–2 zł dla graczy z mniejszym budżetem.

Live Casino a gry mieszane

Formaty łączące elementy ruletki i game showów zdobywają około 7–9% rynku live w Polsce, a część z nich, jak hybrydowe koła z losowaniami, dostępna jest także w Betonred kasyno 2026.

Udział online w podatkach od gier

Z danych MF za I–II kwartał 2026 wynika, że podatek od gier online sięga już ponad 1,5 mld zł rocznie, z czego znaczną część generują kasynowe gry losowe – silnie odwiedzane polskojęzyczne strony kasynowe i projekty typu Vulcan Vegas kod promocyjny bez depozytu 2026.

Średnia liczba graczy dziennie w top crash

Najpopularniejsze nowe crash gry w kasynach obsługujących Polskę notują dziennie PayPal portfel 2026 nawet 50–100 tys. rund globalnie, z czego kilka–kilkanaście tysięcy wykonują użytkownicy z Polski w godzinach popołudniowych i wieczornych.

Konwersja rejestracja → depozyt

Według danych afiliacyjnych 35–50% nowych kont na polskich stronach kasynowych przechodzi do pierwszej wpłaty; serwisy, które jasno komunikują licencje, ryzyka i bonusy – w tym brandy jak kod promocyjny Verde casino 2026 – notują lepsze wskaźniki FTD.

Popularność gier z funkcją „buy feature”

W 2026 roku około 25% slotów w Polsce oferuje „buy feature”, a użytkownicy kasyno Apple Pay 2026 korzystają z tej opcji głównie przy stawkach 1–5 zł na spin.

Średni ticket depozytu mobilnego

W depozytach mobilnych dominują kwoty od 50 do 200 zł, co Paysafecard jak wpłacić 2026 odzwierciedla preferencję polskich graczy do częstszych, ale mniejszych wpłat zamiast rzadkich, wysokich transakcji na konta kasynowe.

It had long been on my wish list to snatch a flavour of one of our most evocative rivers, carving its way through the heart of the North Island. The mighty Whanganui, New Zealand’s longest navigable river, stretching for 290km from its genesis as an alpine stream on the slopes of Mount Tongariro. My first foray with the awa began by following its lower reaches, from Whanganui to Pīpīriki on the winding trail of the Whanganui River Road.

It’s an intimate, authentic and picturesque 64km-long riverside romp that feels charmingly removed, aloof – even defiant to the bustle of modern life, where small river communities steadfastly beat to their own pace, while honouring their natural and cultural heritage. With the visual panorama of the Whanganui National Park enrobing you, there’s no other riverside scenic driving route in New Zealand quite like it. It took 30 years to construct and finally opened in 1934.

An early frisson is driving over the crest of the hill from Upokongaro to be greeted by the Aramoana Viewpoint, serving up ravishing views of the grandeur of the river valley, the fiord-like march of the river, and Mt. Ruapehu, gleaming on the eastern horizon. You’ll pass by a multitude of Whanganui River marae starting at cute-as-a-button Pungarehu, where the whare tupuna was built in 1905 and houses one of the last historical waka used on the river. I shimmied by Oyster Cliffs, an aptly captivating name for the sheer cliffs that dramatically rise up from the road. They are layers of fossilised oyster shells, as the region was once seabed that’s been uplifted.

Before long, I arrived at my riverside roost for the night, the Flying Fox Retreat. No accommodation experience that I’m aware of cuts such a striking first impression, quite like this place. After entering the driveway to park the car on the eastern banks of the river, your means of access to the retreat is by suspended cable car, strung across the river. Sound the gong and the cable car soon whisks across to meet you.

The reverberating gong is an evocative throwback to the era when local Māori would also sound a gong to warn of potentially impending trouble. Being hoisted across the moody waters, with my luggage in toe, is quite the opening act! Exceptionally hosted by Jane and Kelly, they took over the retreat five years ago, after it was originally established as an accommodation venture by the former Whanganui Mayor, Annette Main.

Quirky, artistic and rustic, there’s also a touch of the storybook to this whimsical retreat, wrapped in such a splendidly primeval setting. Gnarly chimneyed cottages are perched high on the riverbank, nestled by a mini-forest of fruit trees, groaning with avocados, figs and apples. Perky hens free-range the orchard, while Jane’s magnificent home-baking wafts on the breeze.

I half expected to spot some forest goblins on the curving paths through the bush to the river. There are some venerable old buildings on-site, including the century-old Koroniti post office and the grand old homestead, where Jane and Kelly served up a hearty home-cooked dinner of wild venison. My fellow guests for the night were a vivacious group of women who were undertaking the Mountains to Sea Cycle Trail. The retreat is also popular with canoeists, whether it’s to drop in for the day or overnight. Jane and Kelly offer a variety of packages to incorporate those outdoorsy pursuits.

There’s also a handy on-site shop selling food, treats, preserves, produce and the couple’s artwork; Kelly paints, sculpts and carves while Jane felts and is a photographer. Do they ever rest in their oasis? The Flying Fox offers a variety of accommodation options, but it’s the three self-contained cottages that are prize draws, hand-built from reclaimed materials and comfortably furnished with carefully restored and upcycled items. I stayed in the Riverboat Cottage, which was originally conceived by the previous owner as a place to brew manuka beer.

The cottage has now been recast to honour the venerable river boats that previously plied these waters, as a lifeline to the river valley. The cottage walls are lined with fascinating pictures and artefacts paying homage to the past. With a second story bedroom, I slept contentedly in my queen size bed, overlooking the river. The living area downstairs boasts a roaring wood burner, fully equipped kitchen and an eclectic mix of CDs, LPs and books to ramp up the sweet sense of escapism. www.theflyingfox.co.nz

The following morning, after savouring the celestial spectacle of that dawn mist brooding on the river, I farewelled The Flying Fox and headed further upstream, bound for Pīpīriki and a half-day tour with Whanganui River Adventures. I tootled through Rānana which is now the largest community along the road. Nearby, Moutoa Island, the scene of a short and fierce battle in 1864 between Whanganui Māori.

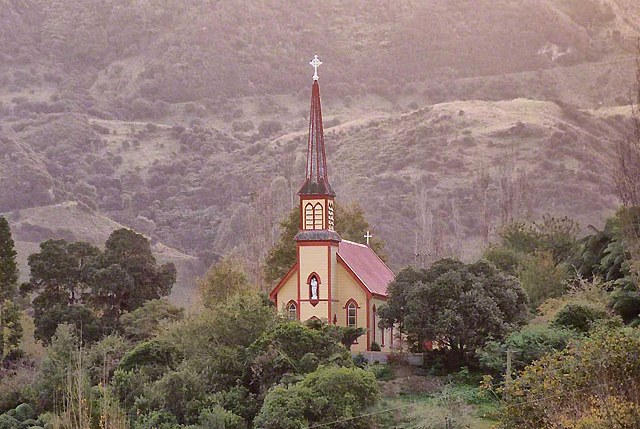

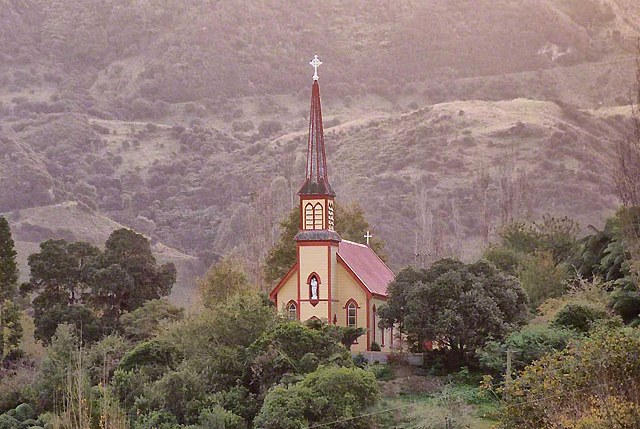

The photogenic glory of Jerusalem, also known as Hiruhārama, reflected in the water as I approached the settlement, home to the century old St Joseph’s Catholic church and convent built in the 1890s. The church features a beautifully carved altar of Māori design and kōwhaiwhai panels adorn the walls. Marist Missioner, Mother Mary Joseph Aubert did wonders here. Her compassion, drive and respect for Māori elevated their health and childcare not only on the river, but later in Wellington.

Aubert was the founder of New Zealand’s only religious order, the Sisters of Compassion. She also set up a thriving business in Māori herbal medicine. Her secret formulas went with her to the grave. She is now on the path to the saintahood, with her “application” before the Vatican. Jerusalem is also synonymous with James K Baxter’s commune, which closed soon after his death in 1972. Pulling into Pīpīriki, as the gateway to the upper Whanganui River, a hive of operators were gearing up for the day.

I was joining the Bridge to Nowhere Tour with Whanganui River Adventures, which is operated by two local legends, Ken and Josephine Haworth. They live and breathe the river, having lived in the middle reaches of the river valley their entire lives. Rich historic tales have been passed down their respective generations, so their tour experience is loaded with indelible family insights. Ken has been driving commercial jet boats for over 35 years, so I felt in the safest of hands on these mystical waters. Operating the only local Māori-owned commercial jet boat touring business on the river, it is not just their seasoned experience, local knowledge and worldly reverence for the region that gushes forth, but also their deep aroha and respect for the river.

My half-day tour not only felt highly personalised but authentic. You could not wish for a richer experience. As we made our way through the wilderness reaches of the river, en-route to the Bridge to Nowhere, Ken regaled our group with enthralling anecdotes, highlighting the characters who made their mark on the river, its shifting fortunes, the natural splendour and the venerated Māori history. This is papa country. The land surrounding the river is only about one million years old, formed from soft sandstone and mudstone (papa) from the ocean-bed.

Eroded by water to form sharp ridges, deep gorges, sheer papa cliffs and waterfalls, mop-topped with a broadleaf podocarp forest, the verdant visual symphony is a constant as we purred upstream. Tree ferns and plant life cling incredulously to the cliff faces, growing at improbable angles. I learnt how Māori cultivated the sheltered terraces and built elaborate eel weirs along river channels where eels and lamprey were known to converge. Ken pointed out the round holes of toko (canoe poles), stamped in the papa cliffs, to help them navigate the wild rapids, over the course of hundreds of years.

Every bend of the river had kaitiaki (guardian) which controlled the mauri (life force) of that place. We skirted into some tributaries that felt so lost-in-time, I half expected a fleet of fully-crewed waka to emerge on the water to greet us. There is an unmistakeable sense of something special about the place, a depth of mood, a certain energy that accentuates the drama of the encounter, particular in the deeply incised gorge. The first significant European influence arrived with missionaries in the 1840s. By the 1890s, a regular riverboat service began carrying passengers, mail and freight to settlers on the river between Taumarunui and Pīpīriki and a booming tourist trade soon began between Mt. Ruapehu and Whanganui.

Ken introduced us to one of the towering figures of this time, Alexander Hatrick. His first steamer, the Wairere, made her first trip to Pipiriki in 1891, evolving into his 12-strong fleet of riverboats connecting Whanganui with Taumarunui. In 1892, Hatrick was contracted by Thomas Cook & Son to carry tourists on the paddle-steamer PS Waimarie. (That vessel was gloriously restored in 2000 and operates cruises from Whanganui on the river’s lower reaches.) Billed as “The Rhine of New Zealand,” the river was a burgeoning artery, the major highway, moving goods and people between Whanganui and Taumarunui. A combination of the road and the main trunk railway opening up cratered demand for the riverboats, which finally stopped operating in the 1950s. But their legacy is unforgettable.

Ken remarked that you will still see haybales and even sheep shifted down the river by jetboat. After taking our fill of the river’s majesty, we tied up at Mangaparua Landing, for our gentle 40 minute walk through the magnificent podocarp forest to reach the Bridge to Nowhere, intimately shadowed by fearless North Island robins, eager to grab the grubs unearthed by our footprints. Splashed in sunshine and thickly bracketed in tree ferns, it’s a pinch-yourself setting.

The Mangapurua and Kaiwhakauka valleys were rehabilitation settlements where land was offered to returning soldiers from WWI. The back-breaking endeavours of these pioneering settlers, clearing much of the virgin forest for farmland, is exhausting just to contemplate. At its peak, there were 30 farms in the Mangapurua, the valley of broken dreams. Today, only a few chimneys, exotic trees and hedges mark the remains of the house sites.

Poor access, erosion and collapsing wool prices all conspired to force most of the settlers to abandon their farms. The hold-outs finally left in 1942 when the government refused to maintain the storm-battered road. The historic arched Bridge to Nowhere, a great slab of stylised and suspended concrete straddling the Mangaparua Stream, was finally completed in 1936 after many years of toil, in a bid to improve road access. But it was all too late.

By the time the bridge was finished, the lower valley had already been deserted by the settlers. It’s been a tour de force to reclaim the bridge from the clutches of the bush, which Ken vividly illustrated with some family photos. It’s an iconic structure deep in the wilderness, a totem to epic if not misguided endeavour, and utterly enthralling to experience. www.whanganuiriveradventures.co.nz

I tripped around the North Island in an Avis rental car. Alongside great deals, enjoy Digital Check-in to minimise physical contact with rental staff and Risk Free Bookings allowing you to change or cancel reservations, without fees, for rentals due to start before 19 December 2021. www.avis.co.nz

The drama, diversity and grandeur of the Ruapehu District sets the stage for spectacular year-round outdoorsy adventure, with experiences that cater for all age ranges and abilities. Blessed by two national parks – Whanganui National Park to the west and the world-heritage wonder of Tongariro National Park on its eastern flank, make your first stop the region’s official website. www.visitruapehu.com

Recent Comments